The Constructivist Motif in Western Art

05/09/2019 General

NEW YORK, NY -- Abstraction in art has existed since people first applied pigments to supports from cave walls to animal hides, and geometric patterning carried symbolic weight in Islamic art and in the bark paintings of Haute-Zaire long before the Symbolist movement. A number of highlights from Doyle's sales of Impressionist & Modern Art and Post-War & Contemporary Art on May 14, 2019 offer an instructive narrative of the development of these same concepts in 20th century Western art.

In 1910, as Igor Stravinsky was completing his score for The Firebird, Wassily Kandinsky made his earliest non-objective abstract works. Soon to follow Kandinsky, Kasimir Malevich would found Suprematism, and Natalia Goncharova would venture into creating abstract works and pioneer the Rayonist movement with her life partner, Mikhail Larionov. Europe soon would fall victim to the horrors of World War I, creating hardship and further spawning creative thought on topics of politics, and social change.

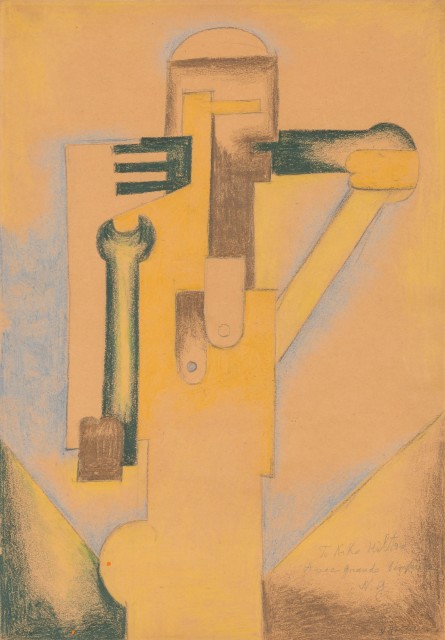

The artists of the time expressed their desires for change through their work. They wrote manifestos, which were followed by passionate discourse. In Italy, Julius Evola, along with the Futurists created works expressing Nationalistic strength and independence. Much like Jacques-Louis David a century before, these artist’s beliefs contributed to shaping forces that would bring suffering and retribution, both internally and from outside. Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque were then creating their earliest Analytical Cubist paintings in Paris. Fernand Leger would absorb Cubist concepts and develop his own unique language. In Tete de Femme (lot 1054), we see Leger fully developed in his mature style arising from Cubism, as well as his use of a patchwork of colors breaking up the picture plane, drawn from Synthetic Cubism and the Dada movement.

After World War I, Europe went through a time of rebuilding. Along with the economic and emotional hardship left behind by the war there was also a birth of new hope for better times. Under the Weimar Republic in Germany, great minds gathered in Berlin and exchanged ideas. The Jazz era had begun, and youthful minds wanted a better Europe than what their parents had left to them. The Bauhaus School in Weimer opened its doors in 1919. Under the directorship of Walter Gropius, an architect who had served in the war, a team of avant-garde teachers were assembled. They conceived a world where all aspects of society would be designed by artists whose goal was a perfect marriage of form and function. Though not a student of the Bauhaus, Adolf Fleischmann would be influenced by the teachings of the Bauhaus and develop his own non-objective abstractions such as Untitled, 1963 (lot 2002).

As the Nazi party aggressively seized control of Germany and brutalized its own people and those in neighboring countries, the Bauhaus would close and great intellectuals of all disciplines would flee, first to Paris and eventually to the United States. The Baroness Hilla von Rebay would relocate to New York and seek out Solomon R. Guggenheim to be both patron and founder of a museum for Non-Objective Abstract Art. Rebay, as Director of the Museum of Non-Objective Art, and Alfred H. Barr, Jr. heralding in the new Museum of Modern Art, New York soon became a place of interest for Europe’s great modernists. But modernist American artists still struggled for acceptance, and especially hoped for inclusion by Barr and MoMA.

As Nazi Germany fell, and the United Nations gave the world hope for continued peace in Europe, young American artists, some benefiting from the GI Bill, would enter a time of celebration. Artists such as Franz Kline would eventually gain recognition and develop a unique American modernist style born out of Surrealism and an expressionist manner of painting, for which the terms of Action Painting and Abstract Expressionism were coined. This energetic style would in turn influence another generation of artists in Europe, such as Jean-Paul Riopelle, Zao Wou Ki, and Hans Hartung. P1960-48 (lot 2032), created by Hartung in 1960 is a prime example of the artist’s energetic drawing style, building a composition of multiple lines harmonically woven together.

Just as the European artists found their response to Abstract Expressionism, so too American West Coast artists found their own voice in the dialogue. Richard Diebenkorn worked in Abstract Expressionism, then expressive figurative motifs before developing a style of abstracted landscapes called The Ocean park series. Though short lived, the Ocean Park works by Diebenkorn are among his most celebrated works, for which Untitled, 1975 (lot 2033) is a great example.

For most movements, the energy captured by the artists is a very finite commodity. This has never been truer than with Abstract Expressionism. Younger artists tired of the style and moved on to other interests more in line with the prospering, manufacturing-focused post-war America. Pop Art, Minimalism, and Hard Edged abstraction flourished. Tadasky, and Alvin Demar “Al” Loving made significant contributions in the Hard Edged field of contenders.

It is not possible to declare in advance where, when or in what form the next movement in the long line of abstract art will arise. But as my own humble observations of the hostility that is rising in our society born from a sense of injustice, I suspect young, creative minds among us are envisioning change and a roadmap for a better tomorrow.

Auction May 14, 2019 / Exhibition May 11-13

Session I: Impressionist & Modern Art at 11am

Session II: Post-War & Contemporary Art at 2pm